Lucy Tompkins works for the Tribune as a housing and homelessness reporting fellow through The New York Times’ Headway Initiative, which is funded through grants from the Ford Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF), with Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors serving as a fiscal sponsor.ĭisclosure: Steve Adler, a former Texas Tribune board chair, has been a financial supporter of the Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. “We’ll just move to another campsite until they put us on the list,” one woman said, a puppy sleeping on the couch beside her. With no more rooms available at the bridge shelters, they would have to leave the park soon. Near Steve’s camp, a small group of people sat on couches and chairs under tarps, shielded from the sun. The HEAL team, he said, is “doing a good job. “There shouldn’t be too many people out here, shortly,” he said.

The two tents beside his sat empty - his neighbors had also just moved into bridge shelters. “Then I’ll be happy again that I can still stay in Austin and get a part-time job.” “I really want to get permanent housing,” he said, standing at the front of his camp, where he had returned to collect some belongings he left behind. He had been moved out of several encampments and was ticketed by police for violating the camping ban before he was connected to a room in a bridge shelter through HEAL while camping in the park. But housing had become unaffordable for him, and a couple of years ago “things fell apart,” he said, and he wound up homeless.

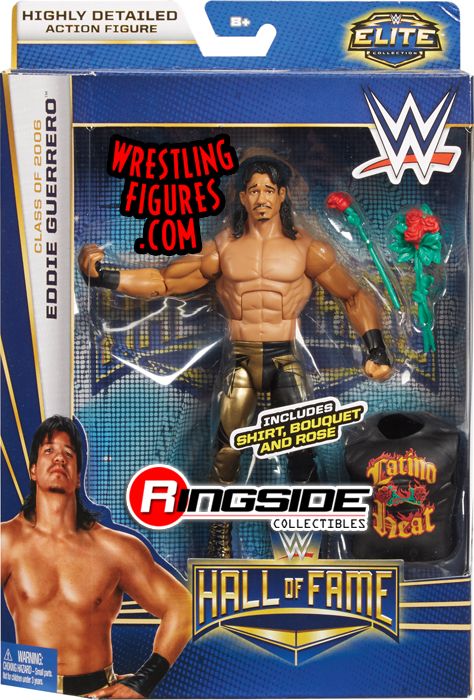

#EDDIE GUERRERO ACTION FIGURE FULL#

Steve, who is 67 and did not give his full name, said he has lived in Austin for 40 years and used to run a tire business. 18 to collect some of his belongings after being given a room in a former hotel that the city converted into a temporary shelter. Steve at his living space in the Guerrero Park encampment. Over the past year, Steve watched from his tidy camp on a small hill as the encampment at Guerrero Park grew and then shrank around him. HEAL has so far moved more than 300 people from encampments around Austin into bridge shelters and nearly 100 from the shelters into apartments of their own. From there, they can eventually move into apartments paid for with temporary housing subsidies from the city. City crews had hauled away garbage and debris.Ī city initiative created in early 2021 called Housing-focused Encampment Assistance Link, or HEAL, has helped about 70 people move from the encampment to the city’s bridge shelters in former hotels. On a recent morning, areas that had been full of tents and furniture were empty, with flattened patches of grass the only sign that people had been living there. “It’s critical that we move the needle significantly on this issue, because there are people who have been waiting for housing and services for years.”Īt Guerrero park, the encampment has been steadily shrinking. “We are really on the cusp of beginning to move a tremendous amount of resources into the community,” Grey said. This much new housing could have a lasting impact, said Dianna Grey, director of Austin’s Homeless Strategy Division. The community, which isn’t part of Finding Home ATX, is adding several hundred new units that will be available next year, and in October, it will begin another expansion to add 1,400 more homes. The majority of housing programs for people coming out of homelessness in Austin have relied on private landlords who will accept housing vouchers, which has become increasingly difficult in the city’s tight rental market.Īnd in northeast Travis County, the Community First! Village, a master-planned community of micro-homes and RVs created by the nonprofit Mobile Loaves & Fishes in 2015, is home to more than 300 people who used to be chronically homeless. In Austin, most people living on the street or in shelters have already been assessed for housing and are on a waiting list that averages about eight months. The elephant in the room is the same as when we started.” Austin investing in more housing

Many people, some of whom had relocated several times already, picked up their belongings and walked across Pleasant Valley Road and into the woods of Guerrero Park. The Parks and Recreation Department wrote in an operations plan obtained by The Texas Tribune that because shelters and housing programs were full, none of the people in the camp would be offered shelter during the cleanup, which would cost an estimated $30,000 and would likely push people “only a short distance from the current encampment.”

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)